Menstruation in medieval times – A practical experiment

Today we are talking about menstrual hygiene in medieval times!

As a hobby living historian that is into historical accuracy a lot, I do a lot of things for my hobby that may seem a bit…. wack. And one of those things I will talk about today. I tried using medieval menstrual hygiene products!

I was very inspired by Abby Cox’ video a while ago, in which she recreated an 18th century period apron. I had always wanted to try out menstrual hygiene products for my period of impression (pun not intended) but I always chickened out and frankly, with an office job that wasnt really something I could easily do over more than a day. But since we are in lockdown for a bit longer, now is the time to do it!

A short disclaimer: I am mostly talking about menstrual hygiene in a christian dominated society in middle Europe in high and late medieval times, because with our focus being everyday life of the mid 14th century in Austria and Germany, I am not qualified to give you a lot of information on early medieval menstrual hygiene or menstrual hygiene in other periods of human history or in other cultures.

In the 14th century, the overall understanding of medicine was heavily influenced by humoral theory. That was a medical tradition taken over from ancient greek and roman medicine when scholars such as Hippokrates and Galen formed or rather wrote down the main ideas of humoral pathology that were still prevalent in medieval times. Some roots of this theory go much further back in time to for example Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia.

There is A LOT to say and read about humoral theory out there on the net, so I will not wrap that up here, but to give you a very basic understanding, physicians back then believed that the human body was influenced by 4 humours or vital bodily fluids, blood, yellow bile, black bile and phlegm. The humours needed to be in a delicate balance in order for the body and mind to be healthy. Once one was present too much or too little, the balance would be lost and people would get sick or at least would change, physically or mentally.

People believed that you could influence this balance by following certain diets and certain behavioural routines, that also included physical activity, personal hygiene etc. and of course medical applications.

And they believed that you could help the body to shed the toxic fluid amounts by draining them. For example by bloodletting and bloody cupping or leeching and also that the body would shed the humours naturally. For example male bodies were thought to grow hair on all kinds of body parts (mostly the face) and that would bring these imbalances out of the body and that female bodies menstruated for that purpose.

So menstruation was seen as a sort of “cleaning” process of the female body in order for it to remain healthy and that is actually something that is still believed today, although that does not really correspond to what we know about medicine. They also thought that menstrual blood was unclean (because basically it was supposed to be full of toxins) and that retaining it in the body was not healthy and – oversimplyfied – that the region “down there” needed to be “aired” well at all times and not to be clogged up by fabric. And that was another reason for women not to wear pants or underpants in everyday situations. (And I truly hope that you can see all the underlying misogynist ideas behind this pattern of thinking.)

When people start talking about menstrual hygiene in the middle ages online, often you will find that the discussion at some point starts evolving around the question wheither or not menstruation was actually a daily thing that people had to deal with back then.

Depending on which source you ask, the menarche or the first menstruation was believed to set in between the age of 9 and 16 and menopause was expected to arrive between 45 and 50. That means that we have around 30 years of cycles to cover. Now usually, women were married when they reached adulthood, so at around 17 to 20 years old and the average high to late medieval family had between 2-4 living children (again, depending hugely on the specific living circumstances and the sources you ask), meaning, that – including a high infant death rate which meant up to double of that amount worth of pregnancies and nursing periods – most women would have several years of their adult lifes in which they did not menstruate. Also, physical activity, physical constitution and malnutrition could have an influence on the number of periods and the amount of menstrual discharge, but not all people back then had to do hard physical work and malnourishment was certainly the exception rather than the rule of medieval daily life. So that leaves at least several years of monthly periods to be dealt with.

As we heard in our introduction about medicine, clearly, they did not know a lot about WHY menstruation happened back then, but they DID know through observation that menstruation was a normal thing and that its absence was NOT normal and that something was probably going on if the menses was absent. So even medieval people thought that some amount of bleeding was a normal, daily occurence. In medieval books about medicine, we often find recipes and guidelines on what to do if the menses is absent or too strong or too light or if you have menstrual cramps and all of the other “fun” problems that menstruation might bring with it, so we can savely say that people had to deal with all kinds of menses problems that we still know today.

If you would like to know more about women’s medicine in medieval times, I highly recommend these two books:

- A translation of the “Trotula”, a gynecological compendium from the 12th century that was – allegedly – written by a female physician, Trota of Salerno, who studied and tought at the famous medical University of Salerno in Italy.

- A translation of the “De Secretis Mulierum” or “Womens Secrets” by Albertus Magnus, another well known gynecological text from the middle ages.

So while we know with high certainty from all the sources describing and showing womens clothing, that women back then did not wear panties on a regular basis – as they also did not do until the 19th century – they must have dealt with all of that somehow. Free bleeding and whiping would of course work if you have a light flow and dont have to do a lot of physical work all day and we know from sources and personal records that until the early 20th century, free bleeding was definitely a thing for some. Bathing and washing (WHICH THEY ABSOLUTELY DID!) can also help keep everything easier even with menstrual hygiene products, but they must have had some kind of contraption to catch discharge before ruining their dresses. Plus, there was also other circumstances to cover for, like f.e. lochial flow (that means bleeding and vaginal discharge for several weeks after giving birth) and incontinence that is also a very common problem after pregnancy.

So what evidence on hygiene products do we actually have?

We know from the mentionned medical works that they did already know of a sort of… vaginal suppository for certain medical applications, but while many take this as a hint to the use of Tampons, there is no evidence that suggests that the concept of a Tampon was already invented at that time and honestly, under the hygienic conditions of the time, that may have been a bad idea anyways, because there is only so much time that it is going to take until you catch an infection or run into a toxic shock syndrome. After all, they did not have the drugstore selling sterile Cotton Tampons back then.

Also, the association of menstrual blood and impureness was not only a spiritual opinion long held in judeo-christian tradition, but also, the humoral pathology idea of medicine considered menstrual blood to be dirty, poisonous and the waste product of an important cleansing mechanism of the female body, meaning that by all means possible, the blood should leave the body as undisturbed as possible.

One thing that we can actually know from textual sources is that they used something they called “menstrual rags”. And we have several sources for that.

One record is from an inquisitional trial in 14th century Montaillou, France, where a woman named Beatrice de Planissoles was caught with blood stained pieces of cloth in her possession that were actually menstrual rags of her daughters that she wanted to put into the drink of her son in law as a sort of magical practice to make him always stay faithfull to her daughter.

Also St Birgitta of Sweden in the 14th century mentions menstrual cloth in her revelations when she says “You will be thrust away like an abortion or a menstrual cloth”, citing thereby a sentence from the bible (in the book of Isaiah). So that could actually be part of a belief from antiquity, but one might argue that Birgitta did at least understand what she was writing about menstrual cloth, otherwise she wouldn’t have mentionned it.

And then we have the physician Bernard de Gordon from the 13th century writing about menstrual cloth twice in his works. In one comment he suggests to use them as a way to ward of unwanted suitors (and I have a feeling that he might be referencing the story of Hypatia from late antiquity or at least a common misogynist theme of warding off men by using menstrual blood, that we also find in other works in history here?) and in the other he also tells women to bring their menstrual rags to their physician so he can inspect the colour of the blood in order for him to come to a diagnosis for them.

Robin Netherton, costume historian and editor of the amazing costume history and textile archeology book series Medieval Clothing and Textiles, a while ago described in a Forum discussion the find of a grave of an old lady in the huge archeological excavation complex of Herjolfsnes, Greenland in the 1920s. When the anthropologists examined the bones, they found a sort of leather stripe from seal skin between her legs, that was held up at mount pubis and in the sacral region with woolen cords, unfortunately to what those were attatched was undeterminable. Inside that leather stripe there seems to have been some sort of fibre. Wool and plant fibre definitely and they also found traces of moss, although it was not clear, wheiter this could have been a contamination from the dig. Even some of her pubic hair was preserved. The anthropologists thought that this could have possibly belonged to some sort of incontinence pad.

And then we have one recent find in Oslo that is woolen fabric from a latrine that the archeologists suspect to be menstrual rags on their blog. But unfortunately nothing concrete has been published so far as I know it and I can’t tell you wheither this might be just toilet “paper” rags which are also commonly found in latrines.

And finally we have this picture from 15th century swiss “Aurora consurgence” manuscript showing a woman with hitched up skirts, menstruating in the middle of a wheel symbolising the 12 zodiac signs of the year and therefor the 12 cycles of menstruation of the year. And in her hand she holds something red and folded, that may actually be menstrual rags! A very exciting illumination, truly!

And then we have the sumptuary laws of Nikolaus Cusanus for nunneries in 1450 where he writes that the nuns may wear woolen underdresses for day and night, but during their “female sickness” they may use linnen underdresses and linnen sheets.

Ok so the evidence is scarce, but not as scarce as one might think. I think these sources already give us a good hint that textiles were definitely playing a role here and the main question that I have is how to hold up such a menstrual rag, so it stays in place during the day.

So here is what I figured out for my practical application of menstrual hygiene:

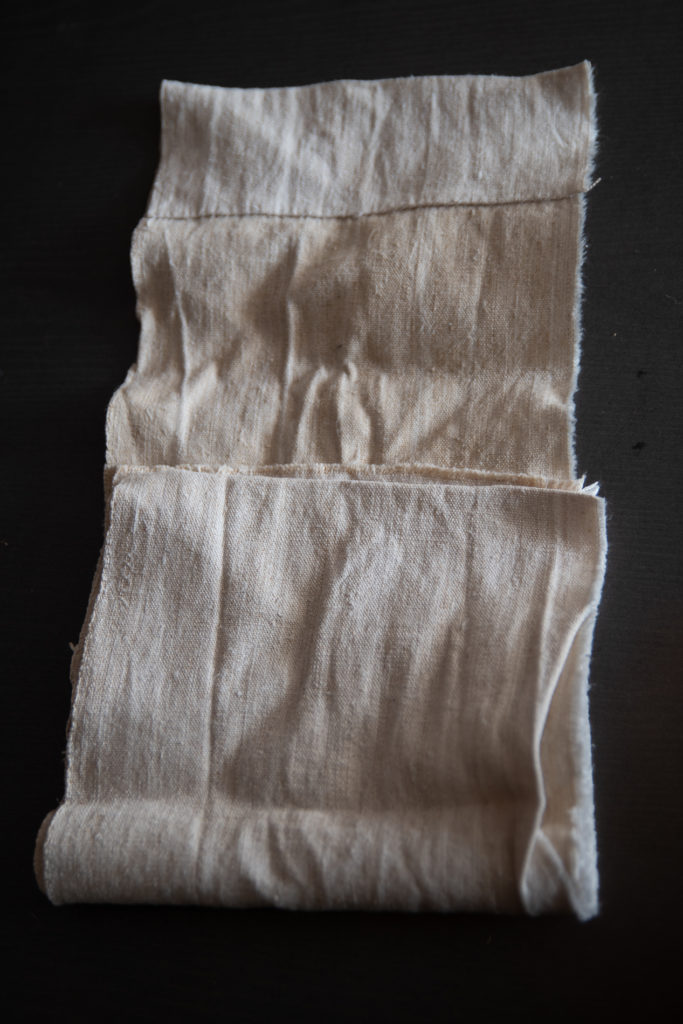

I made some simple menstrual rags from old pieces of clothing and left over linnen fabric that I had at home because I figured that using old, worn out garments or pieces of household linnens would be the way to go for medieval people as well. I am also taking a hint from finds of toilet “paper” rags here that usually consisted of old, cut up fabric as well.

And inspired by the Herjolfsnes incontinence pad and 19th century originals, I made this moss pad that is filled with Sphagnum moss and can soak up a lot of liquid until the moss is saturated. Sphagnum moss was historically used to dress battle wounds (hence the popular name “blood moss”), it is antiseptic and can take a large amount of liquid. It works like a sponge, but is available cheaper and can simply be replaced. So that makes it perfect for the use in pads.

Then I made this belt that will go around my waist, from woven hemp after breech belts that were in use at the time. It has a simple tie to open and close it easily, even if I were to operate under my skirts if I needed to exchange the rags.

And for the “holder” that went inbetween my legs and was to be held by the belt, I had two different solutions. A long strip of broad cloth with a tunnel on one end, that I could use like a loincloth and tuck it into the belt.

And this model with which I oriented myself after the find from Herjolfsnes and after original Padholders from the 19th century. A strip of double layered linnen (which is easier washable than the leather strip of the original) with ties made of leather at the ends that I could take off if I needed to wash the holder. The ties would then attatch to the belt.

And finally, I had a little bag of moss that will be stored with the rags and the holders so I can build new pads on the go.

I tried these menstrual hygiene products while wearing long skirts, doing long walks and light household chores for two full days and I have to say I was pleasantly surprised, how well it went, although I needed a lot more rags than I had anticipated. The pads were really great for my days of heavy flow and felt much more secure than the rags. The broader loincloth holder was kind of uncomfortable especially when sitting since the linnen crinkled and then did not unfold any more. Woolen fabric has more elasticity and would have maybe worked better for that purpose. The narrower strip after the Herjolfsnes find idea on the other hand worked very well and I could hardly feel it while wearing it. I definitely preferred it to the loincloth style.

After the experiment, I handwashed all the rags and pads with historical washing methods (hot water, soap and lye) and it worked very well. Only light staining remained on the linnen fabric that can be further bleached by sunbleaching, as would have been standard for medieval washdays.

Further reading:

Rosalie Gilbert on feminine hygiene

Tempus es locundum on menstruation in medieval times

Monica H. Green, “Flowers, Poisons, and Men: Menstruation in Medieval Western Europe”

The 15th century Aurora consurgens manuscript, Thomas of Aquin

On the history of menstruation

Monica H. Green, Medieval Gynecological Texts: A Handlist

Making womens medicine masculine – Monica Green

19th century moss pad production

Agostino Paravicini Bagliani – Le corps féminin au Moyen Âge

A sanitary compresse from the neolithic age

Related Posts

The following posts might interest you as well: